The Archive is Spinning

Petre Mogoș and Laura Naum (Kajet Journal)

‘The City is Spinning! Timișoara’s Print Ecologies Then and Now’ explores the interconnected history of Timișoara’s print industry within the broader context of the city’s changing material conditions, emphasising its role as both an influencer and product of industrial ecologies across different sectors. Presented in an interactive, non-linear timeline format, the project highlights the importance of micro-histories and challenges traditional historical narratives, underscoring the adaptability of historical narratives in shaping our understanding of the past and future. In this essay, Petre Mogoș and Laura Naum of Kajet Journal reflect on the importance of using design to interrogate and reconstruct archives.

Timișoara’s complex histories describe a city in flux; a city with a changing metabolism and a certain type of vitality that not all cities possess, one that informs and is informed by both global resource networks and local industrial ecosystems. At the core of these transformations has been, since the eighteenth century, Timișoara’s multifaceted printing industry: a dynamic force, serving as a significant node within a broader industrial network that defined the city. Hailed as the ‘Manchester of Hungary’ by economist Lendvai Jenó for its remarkable industrial expansion, Timișoara boasted one of the most diverse, cosmopolitan, and dynamic print cultures in the region at the turn of the twentieth century. Prior to World War II, a total of 584 newspapers were published. The majority of them were in languages commonly spoken in the area—138 publications in Romanian, 163 in German, and 176 in Hungarian. Additionally, there were approximately 100 bilingual or trilingual publications; five in Serbian, one in Bulgarian, and one quarterly in Esperanto.

What sets Timișoara’s print culture apart, alongside its evident cosmopolitanism, is its embeddedness in local and regional industrial ecosystems. Timișoara’s periodicals are more than just passive observers that chronicle the city’s evolution. They go beyond documenting its transformations, evident in the millions of printed pages dedicated to local affairs. Instead, they emerge as active participants, shaped by the city’s interconnected industrial infrastructure, and directly contributing to the generation of new developments. This underscores the imperative of situating them as both expressions of culture and of industry, within a broader context that is enmeshed in wider and more complex historical, industrial, and political webs that span from the era of Habsburg dominance to the contemporary landscape of post-socialist neoliberalism and the challenges brought forward by global digitalisation.

It comes as no surprise, then, that the beginning of Timișoara’s printing legacy is intertwined with the city’s colonial ties with the Habsburg empire. The establishment of the first printing presses in 1771, 1787, and 1851 respectively was contingent on the hard to obtain imperial privileges that only few colonial settlers or wealthy merchants benefited from. Without these influences—be they Ottoman until 1716, Habsburg until 1919, socialist in the second half of the twentieth century, capitalist after 1989—it is difficult to envision how Timișoara would have evolved into a cultural and industrial nucleus. Consequently, a nuanced examination of Timișoara’s cultural landscape cannot afford to disregard these transformative influences.

For our physical installation titled ‘The City is Spinning! Timișoara’s Print Ecologies Then and Now’, we employed various chronologies that shed light on these transformations and give voice to previously overlooked narratives in Timișoara’s otherwise rich print culture. Anchored in archival research, our methodological approach involves reassembling Timișoara’s print legacy through the utilisation of a meta-mechanism: we exclusively rely on printed material in order to make sense of print as a medium. Drawing on historical records dating to as early the nineteenth century up until today, including newspapers and magazines, we piece back together an otherwise scattered and fragmented cultural history. Three timelines resulted from our research: the industrial history of Timișoara, providing a contextual backdrop of the entire industrial landscape of the city; the social history of Timișoara zooming in on print industries, their material infrastructure, and the evolving role of print as a trade undergoing professionalisation and unionisation; the cultural history of printing, spotlighting print culture as a form of knowledge, artistic, and cultural production.

This approach, situated at the crossroads of critical mapping and archival research, is not unfamiliar to us: as editors of Kajet (a printed journal focused on unearthing Eastern European intersections and encounters), we engage in processes of self-historicisation, and of writing and documenting the histories around us; while as archivists of Camera Arhiva (an archival platform that digitises Romanian printed matter published between 1945 and 1989), we speculate about what archives could potentially mean by contesting the expectations of grand historical narratives. Through both projects, the act of archiving is brought forward as a means of uncovering social realities that are often brushed aside from dominant narratives, and as a means of exploring futures that perhaps never came into being.

In this light, our act of archiving (as well as the resulting method of archival research) serves a purpose beyond mere preservation and remembrance. It first and foremost functions as a mechanism enabling us to articulate new futures: a speculative exercise that allows us to reconstruct alternative worlds that have been discarded from collective memory by the status-quo and a linear, teleological understanding of history. To some extent, we aim to consolidate a conspicuously absent history, crafting our own timeline of the past (not in an anti-empiricist or counterfeit way, but in an empowering, imaginative manner). It entails a shift in focus from totalising and totalitarian master narratives toward micro-histories that failed to be included in the official annals of modernity in the first place.

One such forgotten micro-history is, for instance, Timișoara’s clandestine legacy, where local printing presses acted as catalysts for change in times of crisis. While it is widely acknowledged that written text played a pivotal role as the primary form of propaganda employed by the resistance movement against Ion Antonescu’s fascist regime in Romania during the World War II, it is less known that the enduring resistance movement, organised around the infrastructures of the (then illegal) Communist Party, relied on extensive clandestine operations that spanned over a decade and a half. At the heart of these resistance movements was a dynamic print industry operating from the underground. Between 1940 and 1944, the Communists used six covert printing operations, equipped with printing machinery (strategically placed, three in Bucharest and one each in Iași, Brașov, and Timișoara). This afforded a reservoir of experience that very few other anti-fascist political factions could claim. In Timișoara alone, ten publications of the Romanian Communist Party were produced, accounting for half of the twenty communist publications circulating throughout the entire country during that period. The clandestine facilities in the Banat region were instrumental in printing publications of national significance, such as ‘Scînteia’ (The Spark), ‘Dunărea roșie’ (Red Danube), ‘Presa liberă’ (Free Press, later succeeded by ‘România liberă’, Free Romania), and ‘Apărarea’ (The Defence).

Beyond offering an overview of Timișoara’s partisan history, our research also highlights the pivotal role played by printing presses in the union movements and social protests of the Banat region. Timișoara holds historical significance as the birthplace of the first association of labourers in 1868, and in 1921 the printers’ guild achieved a notable milestone by becoming the first regional organisation in Romania to regulate working conditions, institute holidays, and provide compensation for overtime work. It is therefore necessary to position Timișoara’s print industry as a forefront player in broader social phenomena, reclaiming its status as an agent for upholding workers’ rights and protesting against precarious conditions. The first general strike in Romania, which took place around the same time, in 1919, involved over 20 000 workers across the country who followed the lead of printing workers in cities like Timișoara, Iași, and Bucharest. Fast forward half a century later, and Communist authorities took note of print workers’ role in the labour movement, establishing the ‘Printers’ Day’, which has been celebrated every year starting with 1968. The day is not chosen by chance, as it marks the exact 50th anniversary of the 13–26 December 1918 events, when print workers took to the streets in order to advocate for improved working conditions.

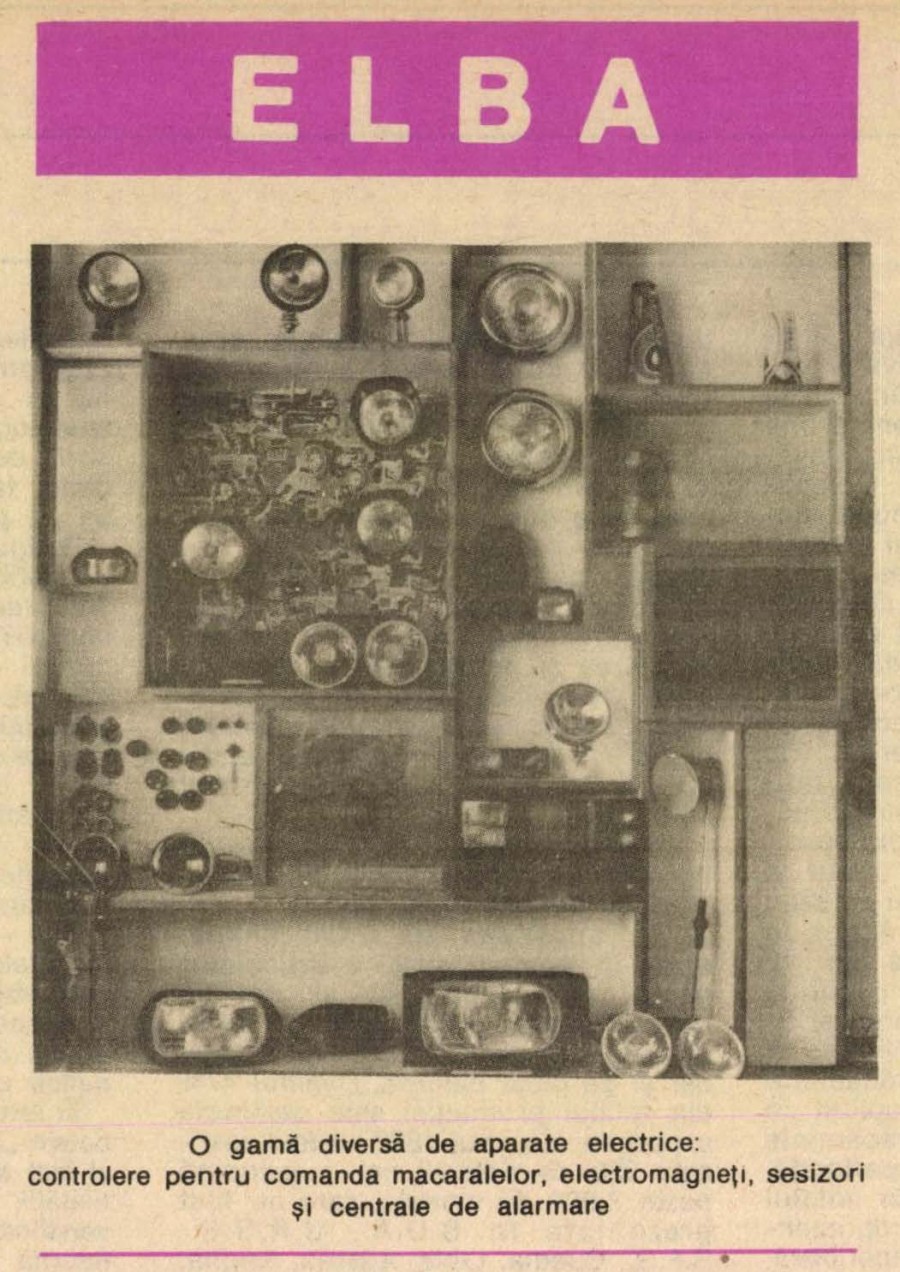

Another micro-narrative that has resulted from our archival research, and that is included in our installation, delves into the close collaborative relationship between local industries and design education in Timișoara. By pinpointing the early 1970s as the formative period when the initial strides were taken to formalise the discipline of design in Romania, archival sources situate the evolution of design in the context of industry: although at first glance distant and disconnected, both fields share commonalities, underscoring a dynamic interplay. This is inter-woven through various key events, such as the inaugural national design conference in Romania, where design principles were officially outlined for the first time, the experimental undertakings of the High School of Fine Arts in Timișoara (summer exchanges, workshops, specialisation programmes, interventions in the public space), the pivotal role played by the Timișoara-based Sigma art collective as a hallmark of a radically experimental pedagogy, and, lastly, the collaborative ventures between high-school students (as designers in the making), their teachers (Sigma members and other artists from Timișoara) and local factories. Among them, we mention Electrobanat, (today, Elba one of the country’s most important lighting companies), 6 Martie (formerly a state-owned company dedicated to the mechanisation of construction works; post-1989, the Timco Halls transformed into a contemporary art exhibition space), and Azur (a paint production company with a rich pre-socialist history; since 2017, the FABER cultural centre operates inside a former Azur industrial complex). Through intergenerational and interdisciplinary collaborations, these entities devised and assembled urban furniture, public lighting systems, electrical tools, packaging for consumer goods, as well as household items like ceiling lamps and television models.

As part of our contribution for the Bright Cityscapes programme, we consciously sought to deconstruct the official threads that articulate what is widely regarded as ‘common knowledge’ with regards to Timișoara’s industrial legacy. To achieve this, we augmented these narratives by identifying gaps and absences, by incorporating new layers of unofficial histories (first and foremost coming from periodicals archived by the Arcanum database and our research project Camera Arhiva). It is precisely because archives are sites of political struggle in their own right—fragmented and incomplete, the result of bias, filtering, and triage, not literal transmissions of ‘what happened’, but a one-sided, mediated (and thus contested) layer of an otherwise complex history—that we need to tread carefully on such grounds. And it is precisely because the archive (supposedly with capital A, akin to History with capital H) is inherently prejudiced, because it is the result of human design and human decision making, and because it is a result of human error and human violence, that the archive needs to be read between its own lines. The patchwork of micro-threads that unfolded in this project not only offers a more nuanced understanding of Timișoara’s industrial heritage, but also serves as a poignant reminder that such narratives (that also come in scraps and bits and pieces) possess the potential to change how history is, on the one hand, recorded and, on the other, remembered.

Text by Petre Mogoș and Laura Naum (Kajet Journal)